Rob Moore

Rob Moore

- Coach Profile

Rob Moore has coaching down to a science in a sport where milliseconds and millimetres count.

Moore is the head coach of the speed programme at Climbing NZ, as well as the company’s high-performance director, and has almost 30 years of experience in coaching climbing.

His passion for the sport is clear and matches his immense knowledge.

He’ll be going to the Paris Olympics with two of his athletes after committing to coaching the discipline of speed climbing after the Tokyo Games.

“Les had a massive library of amazing books, and I’ve still got some of his books today, and I still use some of the books on periodisation,” Moore says.

“He was just such a massive influence on my life that made me want to be able to pass on that same sort of information and have the same sort of environment for my athletes that he used to try to create.”

Moore was eager to set up a high-performance climbing programme in New Zealand and spent many years finding the best way to do that.

“I’ve set up different types of high-performance programmes, trying to get one that worked. Along the way, I’ve learnt more importantly, I suppose, what didn’t work, what was not creating the right environment for success that we were trying to find,” he says.

“So then, finally culminating in this high-performance programme has sort of been the first one that’s really worked and done what we were trying to achieve and been a success.”

The Tokyo Olympics were the first to include sport climbing as an official discipline and controversially combined speed, bouldering and lead climbing into one event. After feedback from the climbing community, the events were changed for Paris, with one set of medals awarded for bouldering and lead and another for speed.

“As soon as Tokyo finished, and they announced that speed climbing had its own medal, I said, ‘Right, I’ve got another chance now to really look at how our high-performance programme is set up’,” Moore says. He enjoyed the challenge of trying to build an athlete who was capable

of both, but it wasn’t the way most competitive climbing nations work.

“I sat down for a week, and I wrote a whole entire document on how our high-performance programme was going to be set up, who I was trying to attract, how we were going to attract them.

“I really just put everything in there, sponsorship, anything like that, everything was covered, what I expected out of the athletes.”

Moore made any athletes who wanted to commit to speed climbing stop lead and boulder climbing a big ask.

“I didn’t want athletes who still wanted to do this hobby side of it; I wanted athletes who said, yes, I want to try to get to the Olympics, and I’ll do anything to try and get there.”

After a few competitions and testing, he was left with six athletes.

“Those athletes knew exactly what was happening, and they were all really fully dedicated; they all embraced the way we were training,” he says.

“What I tried to create right from the start was an environment where we were all suffering together, but we were trying to make fun of that suffering,” Moore laughs.

“We knew we had to get up and do the hard work and do the repetition, but we could do that in a fun environment where everyone got on with each other and everyone had fun.

“Through that struggle and hardship, they’re all sharing that together, so it’s quite important that we created this environment of really passionate, really enthusiastic, hard-working individuals.”

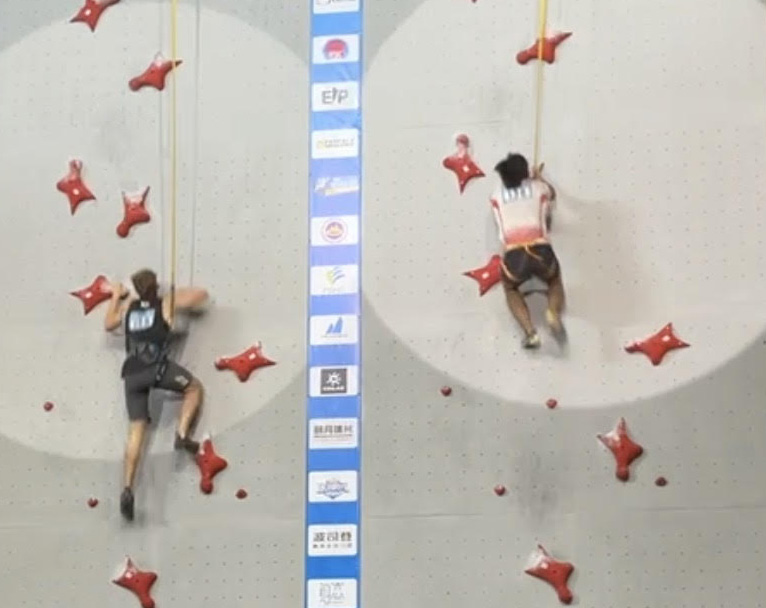

Speed climbing is on the exact same wall every time an athlete climbs. Walls are 15m high and are certified to make sure every single hold, angle, texture and belay is identical to the millimetre with each other.

Before 2019, the closest speed wall for Kiwi climbers was in New Caledonia, so Moore and the Bay of Plenty Sport Climbing Association built an outdoor speed climbing wall in Mount Maunganui. To this day, it’s the only one in the country.

But rain and wind can prevent climbers from using the wall, and Moore found they could only use it for about 30 percent of the year.

“We had this programme running, and we were finding that so often, we couldn’t actually train on the speed wall. We go along with the old adage that sprinters need to sprint, so we use that for our climbing wall as well, you know, climbers need to climb,” he says.

With the support of local businesses and High Performance Sport New Zealand, Moore was able to construct some indoor walls—not quite full height, but enough to train large sections of the climb.

“With the support of all the local community getting behind my passion, I suppose, we were able to get this facility now,” Moore says.

“When we go travelling around the world and training in other countries, we do really have one of the best facilities in the world set up between our two training venues, with far more than adequate facilities for us to train in.”

Speed climbing is still a relatively new sport in New Zealand, and Moore admits he was a bit dumbfounded when two athletes made the Paris Games.

“Realistically, when we started the programme, we had a goal for LA 28, so for us to qualify early just means we get to have all this experience and take in the Games when we’re not putting a ton of pressure on ourselves,” he says.

“I’d just love to see speed climbing growing in New Zealand and some other walls going up. Because our talent pool at the moment is pretty much just from the Bay of Plenty, and I know I’m missing out on so much other talent that’s around but just doesn’t have access to a speed climbing facility.”